|

Painting a contemporary landscape in watercolour Our next art demonstration on 20 February features well-known, Berkshire-based artist, Elizabeth Baldin, who will focus on her approach to painting watercolour landscapes. This takes place at Lacock Village Hall and replaces our usual Thursday night session.

To find out more about Elizabeth Baldin and her work please take a look at her website.

See you at the demo!

0 Comments

Demo date: Thursday 28 November Join us for our last art demonstration of the year, which is being given by Bristol-based painter, Tom Hughes.

An important part of Tom's approach to painting is to work outside on location "en plein air" initially, making small studies in oils, observing and capturing the light, texture and hues, developing the work back in the studio. He paints a range of subjects such as woods, street scenes in London, Bristol and Bath, and beach huts. Demo venue: Lacock Village Hall, East Street, Lacock SN15 2LF Time: 7pm prompt to 9pm Guests welcome - £5 entry fee per person on the door. Next LAG demo - Thursday 31 October Our next demo takes place at the end of October, on Halloween night. It will be an evening full of treats and no tricks.

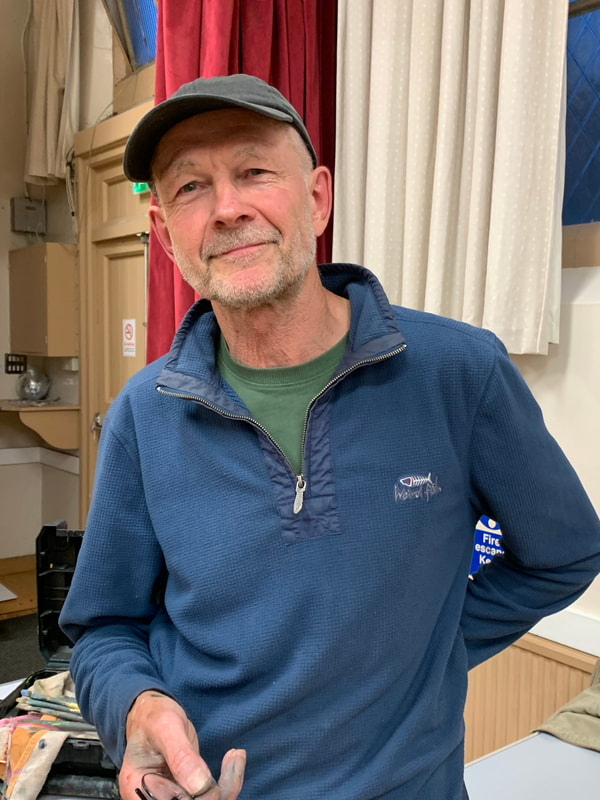

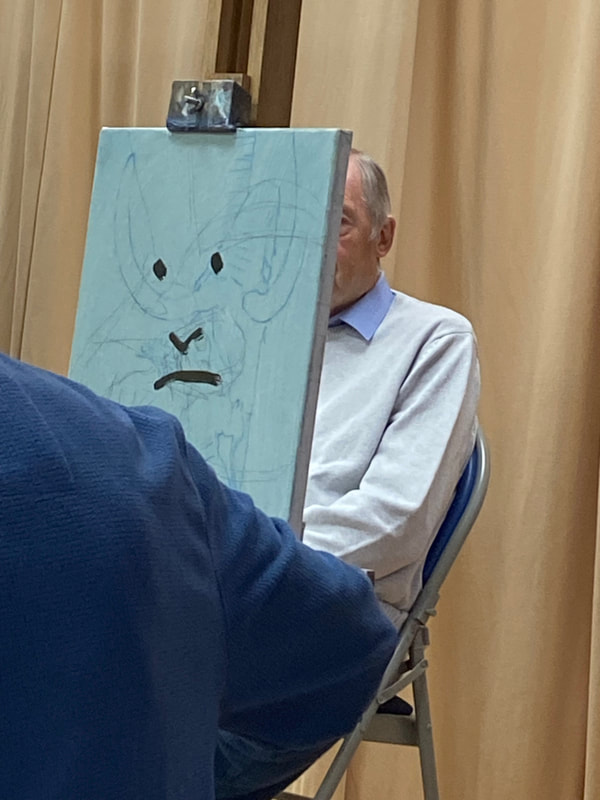

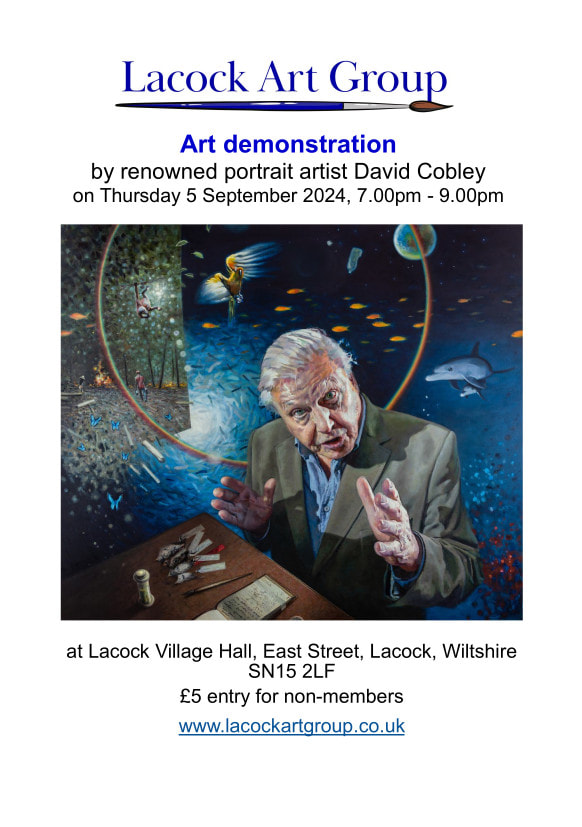

Professional artist Colin Ross Jack will demonstrate his approach to making art with pastels. You can find out more about his work by visiting his website. Guests are welcome to attend - there's no need to book a place in advance. There is a £5 entry fee for visitors, payable on arrival. We look forward to seeing you at the demo. Details are below: Demo sheds light on the painter’s technique and approach David Cobley is an English portrait and figure painter, best known for his oil paintings of famous people including actors, royalty, broadcasters, and leaders of large institutions. Luckily for us, David lives in Wiltshire and this demo came about by chance when one of our members, Ken Baldy, attended a talk David gave to a local business group about his life and work. Chatting after the talk Ken asked about doing a demo for us. And the rest, as the saying goes, is history. Held on 5 September at Lacock Village Hall, this demo is our best-attended in recent years, if not ever. The chance to see a painter of such calibre at work proved highly appealing. With about 40 people present, including some visitors, we ran out of chairs so for a few it was standing room only. The aim of the demo was for David to paint a portrait of a ‘live’ sitter, who we could choose, and show how he approaches his craft. Given that Ken instigated the demo it was only fitting that he was David’s muse for the session. David started the demo with a question for the audience; what did we want him to cover during the session? His technique and thinking, was the answer. Equipment With Ken in position sitting on a chair on the hall’s stage, a pale gold curtain as backdrop, and David all set up, he quickly explained about the kit he’s using:

Initial marks He pre-paints a canvas usually with a neutral, greeny blue background, saying that this is partly so as not to feel daunted by a white canvas and it gives a tone to work into. He explains he thinks more in tone than in colour, and this background is 3-4 on the tonal scale where 1 is white and 10 black. David starts the painting by making black marks on the canvas to indicate the position and tonal value of the eyes, nose and mouth, followed by white marks on the forehead, also for tonal purposes. He mixes Prussian Blue (PB) with Venetian Red (VR) to make a darkish grey and advises people to use bigger brushes than you think you need, for faster coverage. Impatient by nature, says David, he likes to see quick results when he paints. The first marks made on the canvas are really important, he says. As he’s never painted Ken before, he doesn’t know what his head looks like so he explores it first. He explains that if this was a normal sitting he would have done some sketches beforehand for exploration. Next he starts thinking about Ken’s head, neck and shoulders and makes a rough outline on the canvas. He also pointed out that, while painting, he constantly flicks his eyes quickly from Ken to canvas and back again, and constantly adjusts the drawing as he goes. He tells us that he has a life size skull at home so is very aware of bone structure and how the flesh falls on a face. Fleshing out Having got the outline down, David changes the paint to Yellow Ochre (YO). He’s now thinking about the contrast of Ken’s pale blue shirt against the warmth of his face and the greeny/blue background so puts YO on the background. For the forehead skin colours he uses a warmer blue than PB, Ultramarine Blue (UMB) and a different brush for each pigment to avoid muddying the colours. Tonally, the forehead is 3 on the scale, he informs us – an overhead light shines on it. He reminds us that the head is asymmetrical so he tends to paint one feature (such as an ear) on one side of the head and checks the corresponding feature on the other side of the face straight away, for accuracy. As he was making adjustments David remarked matter-of-factly that Ken’s neck is thin. Ken retorted, “Well, it’s been wrung a few times!” The audience chuckled loudly, enjoying the banter. Ken pointed out that he’d noticed the high degree of concentration on David’s face when he looks at Ken and back to the canvas. Someone commented that he hadn’t done much to the eyes but nevertheless the likeness is there, just as they are. The best advice he says he’s ever been given came from his school art teacher. He told him to paint what you see, leave your preconceptions at the door. David says he’s conscious the painting looks a mess at this stage, so tries to ignore the messy start and reassure himself that he’s done this before; it will be OK. He need not have worried. Within a mere 20 minutes of starting the painting he had captured a distinct likeness and the essence of Ken. Further refinement After a short tea break we resume. So far he’s used PB, YO, VR for this painting. Responding to a question from the audience about preferred colours, he says he uses PB and VR a lot, but apart from those doesn’t have a standard set of colours as such. Always aware of complementary colours he tries to bring them out in his work, with this painting the colours are orange and blue. Although working from a photo of a subject can sometimes be helpful David says there’s no substitute for a sitting with the person. In portraits you’re trying to create the illusion of a 3D object in space, using pigment and brushes. That’s hard to do from a photo because it’s a flat, 1D surface. Talking as he works, David explains that he’s trying to suggest Ken’s neck is dipping into the collar. More friendly banter ensues. Ken: “Do I look like a tortoise to you?” David: “I think I need my lawyer!” “You’re coming out of your shell, Ken,” quips someone in the audience. As well as painting people David says he loves to get out into countryside and paint the lovely landscape of Wiltshire. He also likes to think, and be controversial in his paintings. Now that he adds more detail and refines the painting he uses thicker paint, which you tend to do as a painting progresses. He adds that using paint straight out of the tube is probably the best approach from a permanence standpoint as it has been mixed specially for this purpose. Asked how to avoid over working or flattening out when painting from a photo, he replies, “Good question. I suppose it’s experience, knowing when to stop.” The session went in a flash and suddenly it was 9pm, time to stop. Feedback from attendees was overwhelmingly positive, saying the demo was “superb”, “amazing”, “fantastic”, “great to listen to – gave us factual information but didn’t overdo it”, “a privilege”, “incredible and inspiring”. Our thanks to David for making it such an enjoyable and interesting evening, and to the art group members who helped to make it all run so smoothly on the night. David spent another hour and a half on the painting the following day; his final version is below. It's interesting to see that the relatively small tweaks and refinements at this stage make such a major difference overall. The painting will soon adorn a wall in Ken’s house, if it doesn't already. David's Devizes exhibition starts soon

David is exhibiting in Devizes, at the White Chalk Gallery, 5 Old Swan Yard, SN10 1AT, from 17 Sept – 5 Oct 2024, Tuesday to Saturday, 10am to 5pm. Called Traces, the exhibition also features ceramics by Janene Waudby. More information is available on David’s website, where you can also buy a copy of his book, All by Himself. It’s a fascinating read, discussing his artistic influences and putting his work into an art historical context by charting his work through key stages of his career. Join us on Thursday evening, 5 September at Lacock Village Hall This chance to see well-known Wiltshire artist, David Cobley, at work is one that's not to be missed! David, one of England's foremost portrait and figure painter, will be painting a portrait in oils, working with a live model on the night, explaining and demonstrating his approach. He has been commissioned to paint many famous personalities during his career including comedian Ken Dodd (a remarkable painting of reflections now hanging in the National Portrait Gallery), broadcaster Sir David Attenborough to mark his 96th year, The Princess Royal, and artist David Hockney, as well as lesser-known people.

He is driven by his fascination with the way human beings think, move and behave. His book, All by Himself, discusses his artistic influences and charts his career is well-worth reading. To learn more about David and his work, please visit his website. Here are a few of his portaits, provided by David and including a self-portrait. Details of the demo are on the poster shown. A look back at Kate Wade’s demo for Lacock Art Group Kate is a Wiltshire based landscape artist who specialises in watercolour and gouache, and who also uses acrylic inks, acrylics and oils in her paintings to convey certain characteristics to best effect. She finds inspiration for her work from nature, the countryside and coast, which offer a never-ending variation of colours, patterns and textures through the four seasons. You can see Kate’s work in an exhibition at The Corsham Gallery, in Corsham, Wiltshire, until 28 August. We were very pleased to welcome Kate at the end of May to give an insight into her approach to painting along with some tips about how to apply her technique into our own artwork. Kate used a reference photo taken of Avebury earlier in May, which Kate calls the ‘fluffy month in the countryside. The scene is of distant trees and hedgerows, beyond a bright yellow field in the middle ground, and a dense bank of foliage (grasses, nettles, cow parsley) in the foreground. Her style is very loose and tends to feature fresh, bright colours. Getting started Her ‘go to’ paper is 300g/m2 Bockingford stretched NOT (cold pressed) paper. For the demo Kate uses half a full sheet of this paper, taped to a board. She prefers Jackson’s Art Supplies own brand paint of watercolour paint or Windsor & Newton’s Professional series, and tends to use flat paint brushes. Kate starts off by drawing a light sketch, placing the horizon centrally on the paper – there are no rules, she says. Initially she focuses on the foreground, aiming to put texture here, using masking fluid to block off twigs and other foliage, preparing the base for further layers of paint to give the impression of masses of leaves. Next she spatters masking fluid with an old toothbrush, using a very light touch. Trying not to overdo the cow parsley. The applicator for the masking fluid (which has a small pipette able to mask off quite fine lines) is from Jackson’s Art. After this she moves to the sky and before approaching the bottom half of the painting. Sky and foreground Tackling the sky is always a bit scary, acknowledged Kate; it was comforting to hear that even accomplished, professional artists also find this rather daunting at times. Using a range of different blues, beginning with Cobalt Blue for the stream of blue sky among the clouds, followed by Kings Blue Light, Kate then adds another shade of blue. She softens the edges of the clouds for variation and darkens this with Burnt Sienna, running it into the Cobalt and dabbing with tissue paper to soften it. Generally Kate paints her skies wet on dry, preferring a bit more control over the paint than you get with wet on wet. Now Kate moves to work on the foreground, putting in some acrylic ink, which is waterproof, to represent grasses and leaves. She builds up foliage of nettles etc in layers, making grassy lines with a rigger brush, getting movement into them, mixing Yellow Ochre with Emerald Green. Using a small squirrel mop she makes nettle shapes on the grass before laying a wash. Fields and distant trees Kate next turns her attention to the fields in the middle ground of the composition, first applying yellow, the lighter, brighter colour, to avoid it getting lost. Starting with Cad Yellow Light plus a bit of Indian Yellow (a very intense colour) out of tube to warm it up. She takes yellow over the grassy areas as the undertone and adds yellow to where trees will be on the horizon to give them a little light. Permanent Green, knocked back with Yellow Ochre, keeps this area sunlit and bright while a ground of green will blend in with trees when they’re painted. She uses a bigger brush for the foreground colours that are more saturated and spatters paint to distract eye from hard edges. When this is dry, she paints a layer on top adding Cerulean Blue to the green to exaggerate reality slightly. Once the sky is dry Kate starts work on trees. She spatters and stipples the paint to achieve the effect of soft, fluffy edges on the trees. Getting the right shade of green can be tricky, says Kate, and Hookers Green is an option. For the smaller trees, Kate uses a round brush to blob the paint on, adding a darker colour in middle of the tree. Here, granulation of paint enhances the effect. She adds a tiny bit of French Ultramarine to darken the green further. Foreground depth, finishing off Kate decides to put shadow undertones into the foreground to the bottom half of the painting. To do this she mixes Burnt Umber and Quinacridone Purple, creating a clear, nice dark. Using a big flat brush she paints it across the foreground noting that it may look drastically dark, but the paint sinks in and you can put more colour over the top. Next Kate adds more green to the foreground shadow, keeping the green bright but tempering it with Burnt Sienna. The more opaque the colour the more it sits forward in the painting so she recommends using it to your advantage. The final step is to rub off the masking fluid from the foreground, applied at the outset, to create the grasses. Kate adds more detail with thick Yellow Ochre mixed with white gouache. She also use gouache to create white or pale highlights. Creating the effect of cow parsley is laborious takes time to do, but is worth the effort. To do this Kate uses cotton buds to spatter gouache, a creamy white colour mixed dirty water. With grateful thanks to Kate for an inspirational, enjoyable and educational demo.

REMINDER: takes place on Thursday 30 May at Lacock Village Hall, 7pm.

Guests are welcome - no need to pre-book attendance. Pay on arrival. We are looking forward to welcoming local Wiltshire artist, Kate Wade, for her first demonstration to members and guests of Lacock Art Group. Kate is a contemporary landscape painter who works predominantly in waterolour and gouache. To find out more about Kate and what inspires her work please visit her website, where you can also see some of her brilliant art. Demonstration review Watercolourist Jake Winkle, who’s known for his bold, loose and lively style, returned to Lacock Art Group towards the end of March to demonstrate his approach to painting wild animals. Before going any further, apologies to Jake for borrowing the title of one of his DVDs in the headline of this blog post. ‘Going Wild in Watercolour' is also the title of one of his art workshops at the White Horse Bookshop in Marlborough on 22 May. Jake previously demonstrated his method to LAG in about 2016, and he remembered one or two members who had evidently made a lasting impression on him! This time around Jake created two paintings during the demo; a pair of otters were the main feature, followed by a quicker painting of a cockerel. Equipment To start with Jake gave a brief explanation about his preferred painting kit, as follows. Paper He uses Arches watercolour paper, rough, 140lb/300g/m2 because it absorbs water quickly and evenly, allowing the paint to bed into the surface of the paper in a consistent way. He also stretches the paper to prevent it cockling when applying very wet washes. The paper then tightens up again when the paint is dry. Palette Jake used a portable palette for the demonstration, although a white dinner plate does a sufficient job if you have nothing else – the base of the plate provides a big enough surface to mix paints while the rim holds blobs of paint. He said it’s important to keep the mixing space of your palette away from paint itself so that it doesn’t become contaminated. Easel His easel is home-made, portable and built to his specification, with all the key features positioned exactly where he needs them to be. Paint As he is a colourist Jake, uses secondary colours straight out of tube rather than mixing them to achieve greater intensity of colour. Using the full range of tones and colours is key to his style. The brands he tends to use are Winsor & Newton (W&N) plus a couple of Daler Rowney colours. He uses these brands partly because they are what he started with but also because, in his view, some of the other brands aren’t as thick as W&N out of tube. This is important for his style of painting, which involves applying dark colours straight away, rather than the more traditional approach of building up depth of colour in layers. Brushes Jake recommends using hair (sable) brushes because they create a clearer wash, and hold about three times the volume of water than synthetic brushes. With watercolour, he explained that for optimum results it’s essential to touch the paper with the brush as little as possible. Practice, practice, practice It gets complex when combining all the basic techniques of watercolours so he advises learning how to use watercolours through a lot of practice, to the point where it becomes second nature: you know how the paper reacts to and absorbs water; you can anticipate what happens when wet paint hits wet paper; how watery or thick the paint needs to be, and so on. Only when you are fully familiar with how watercolour behaves can you begin to consider your own artistic interpretation of the subject, which is what makes your art different to others. Painting 1: Otters

Second otter The second otter, on the right of the picture, is very pale, providing contrast. Jake explains that paintings need busyness and quietness, achieved with tonal differences. Instead of grey, he puts in a combination of blue and crimson, wet into wet, to add depth. Spattering paint helps break up patterns and shapes, but also can help bring together the object and background. Making the whiskers overlap onto the second otter also helps to connect the pair. The background is a pale, delicate wash of cobalt blue, a dominant colour in the rest of the painting, helps to unify it and also helps to reveal the otters’ edges. Jake also discussed how he fragments, or breaks up, the image to simplify it, adding that the key to simplification is, in fact, understatement not omission. Find a way to understate the image, not omit elements because that can change the scene, making it unrecognisable. Understatement can be delivered through reduction – reducing lots of small shapes into larger ones by connecting them together, often by tone, and by merging shapes together with soft, blurred edges. Painting 2: cockerel This was a very quick, gestural painting.

Wrapping up It was a pleasure to welcome Jake back to LAG to show his approach. His demo not only proved to be inspirational for the 30 or so members and guests who attended, it also provoked some lively, good natured and amusing discussion from one of our more provocative members on the topic of sustainable art materials! Overall, this demo was tremendous fun, informal yet most informative. If you’re interested in finding out more about Jake’s work please visit his website where you can also find details of the workshops and online tutorials he offers.

A glimpse into the art of painterly screen printing Gail is an award-winning painter printmaker who has a reputation for semi-abstract landscapes designed to imbue a sense of calm, which she creates through screen printing. She delivered a demonstration to members of Lacock Art Group and guests towards the end of January. The focus of the first part of the demo was an overview from Gail of the screen printing process and her particular approach, while the second part involved audience participation giving people a chance to have a go at printing. Gail is, understandably, protective of some aspects of her own artistic process so this blog gives more general explanation of what’s involved. What is screen printing? In its simplest form, ink or paint is pressed through a fine mesh screen to transfer it onto paper (or other surface, such as fabric) and produce an image. The mesh is blocked with something to prevent ink/paint going through in places where you don’t want it to. In this way, an image is built up by printing several layers of different coloured paint, each time masking specific parts of the mesh. You can block parts of the mesh with pieces of paper (newsprint), which can have hard edges or ripped edges to allow a varied effect. For example, if your image is of large stones/boulders you would print, let’s say, three layers, blocking out different parts of the stones at each layer with a different colour, creating light and dark areas that give the stone a rounded effect. The printing process is all a bit experimental so happy accidents can occur; you’re never quite sure how a colour might come out when printed over. Another way to block parts of the mesh screen involves a photographic process. This consists of spreading a light-sensitive emulsion on the mesh. Once the emulsion is dry, you draw your image on a transparent, mark-resistant surface (like an acetate sheet) with black mark-making tools (like graphite or chinagraph) and expose the screen to UV light. The black marks prevents the light from fixing the emulsion thereby creating spaces for the ink to be pushed through. The UV light makes the emulsion harden, and the hardened areas prevent paint being pushed through the mesh – a stencil effect. The emulsion is washed off, leaving clear areas where the paint can be pushed through to print an image. Screen printing has been around for centuries and is also known as silk screen printing, due to its Chinese origins when silk was used as the mesh for creating wood prints. Screen printing was popular in the 1960s, partly because it lent itself so well to making posters and prints of the type featured in pop art. In the 1990s a new, grained plastic was launched that enabled lithographic marks like washes to be created. Monotype v monoprint The two main forms of screen printmaking are with and without stencils. The two different kinds of print are monotype, and monoprint. Gail uses the monotype approach. A monotype print is a unique edition of a single image – a wholly unrepeatable one off. Gails finds this exciting, you build up the layers, and respond to the printed result as you go, which is more like painting. Monoprint has an element of a repeatable matrix - is a print made in a series where the main image is repeated but each print has slight individual differences, marks or embellishments. Essential equipment Gail made her screen printing unit herself, to her own specification. As shown in the photo, it consists of a bed section onto which paper is placed. A hinged frame, containing the mesh screen, sits on top of the bed. There’s a small gap between the mesh section and the bed, known as the ‘snap’, created by attaching a piece of thicker card to the bed at the top and bottom sides. Likewise, registration stops have to be put in position on the bed section to line up the paper and ensure the image is in the same place for at each print layer. A potential issue with using a DIY setup rather than a professional print setup is that paper can stick to the mesh during printing, which can cause unintended marks – known as ‘halos’ - that you may not want. You also need a squeegee rubber blade, to move the paint from one end of the screen to the other and push it through the mesh. Printing surface and paints For screen printing you need paper with a smooth surface, thick enough not to buckle when it’s wet. Gail used a paper called ‘bread and butter’ for the demo but she prints on ‘Somerset satin’, which is a heavy watercolour paper. You can print onto anything, including fabric (think calico bags) but you’ll need to change the squeegee blade and use a 40 count mesh to allow more paint to go through. Gail uses acrylic paints with a medium mixed in to act as a retarder to slow down drying. Screen printing is a fast process because the ink dries on the mesh quickly and blocks it, sometimes where you don’t want it to. Alternatively, you can use watercolour paint, or water soluble pastels. Charcoal and water soluble graphite also work well, says Gail. Getting stuck in As part of the demo, Gail gave members of the audience the chance to have a go at printing, using the screen printing equipment set up in the hall and under Gail’s guidance. Joy Tickell, Victoria Cleverley and Tracy Warne gamely stepped up to the plate, with Joy and Victoria first up doing a double act. Using a variety of colours, they painted directly onto the open mesh with large, random strokes, filling the entire mesh area. They also applied a medium (similar approach as masking fluid) to the mesh to block the places they wanted to leave white when printed. When Joy and Victoria were satisfied with their application of paint it was time to make a print. Gail showed how to hold the squeegee, with the blade at a 45 degree angle to the mesh. Her recommended technique when printing is to stand with one foot behind you and pull the blade down the screen, towards you, pushing down on open aperture. Remember to stop the blade just after the edge of the mesh, and wiggle the blade up slightly before lifting it up to avoid the paint splodging. Joy went first. She applied an initial ‘flood coat’ to prime the mesh with paint – supporting the screen as she pushed the paint down the screen with the blade but without any pressure. After making the first print Joy did another flood coat back by pushing the blade and paint up to the top, ready for the second print. Before Victoria’s turn to make a print, they applied more paint to vary the image, creating a different version of the print. You can see the difference in the images shown. Tracy was next to wield the squeegee. This time Gail suggested not doing a flood back with paint, instead using medium only to create a ghost print that produces a much more muted print. When finished, wipe off the paint from the screen with a plastic knife and reserve it in containers to re-use another time. Wash both sides of the mesh screen with sponge and water to ensure all the paint is removed, ready for the next print session. It was interesting to learn about a technique that most of us are aware of but probably have never tried. Our thanks to Gail for sharing her knowledge with us. You can find out more about her work on her website, where you can see plenty of examples of her amazing artwork.

Exhibition, art demonstrations and member workshop dates Please check out our events page, where you'll find the dates of initial activities planned for 2024. There's much to look forward to, kicking off with a demonstration by Gail Mason in January that will feature screen printing and painting and will be open to guests as well as members. You can find out about Gail's work by visiting her website. Our Saturday workshops for LAG members only, which were introduced in 2023, have proved a popular addition to our activities so we will be holding these again in 2024. The first workshop of the year takes place in February; it will be given by Melissa Wishart and focus on oils. More dates will be added to our events page in the weeks/months ahead so do check back regularly to see what's new. Our last life drawing session of 2023 - a brief review As 2023 drew to a close, at the end of November we were treated to a life drawing session, featuring a lovely model, Joy, who was making a repeat visit to our art group. It was quite a challenge, not only from a drawing/painting perspective but also from a warmth standpoint - it was a very cold evening and the hall's heating wasn't working. Joy was wearing traditional dress, brightly coloured, but designed for warmer weather. Our thanks go to Joy for modelling, for being so obliging, and braving the cold. Here are a selection of the artwork produced on what was a very enjoyable night. So, with a few days' left in 2023 and as 2024 approaches, all that remains to say is happy New Year.

|

WelcomeRead about our latest activities and initiatives here! Archives

February 2025

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

Galleries

- Workshops >

- Challenges >

-

Members' Galleries

>

- Richard Adams

- Ken Baldy

- Keith Bennet

- Graham Brewster

- Victoria Cleverly

- Sarah Clover

- Dave Cooper

- Chris Crosby

- Margaret Gray

- John Harris

- Jacqui Matthews

- Vanda McCann

- Graeme McFaull

- Karen McGreevy

- Glyn Overton

- Sally Parsons

- Linda Ridler

- Karen Road

- Kay Smith

- Joy Tickell

- Jane Tucker

- Elspeth Wales

- Tracy Warne aka Maggie

- Angela Weir Martin

- Mike Wilson

- Exhibitions

- News/Blog

- Membership

- Events

- Contact

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by netnerd.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed